The Ashes Beneath the Halo: Gandhi’s Perverse Purity Test!!!

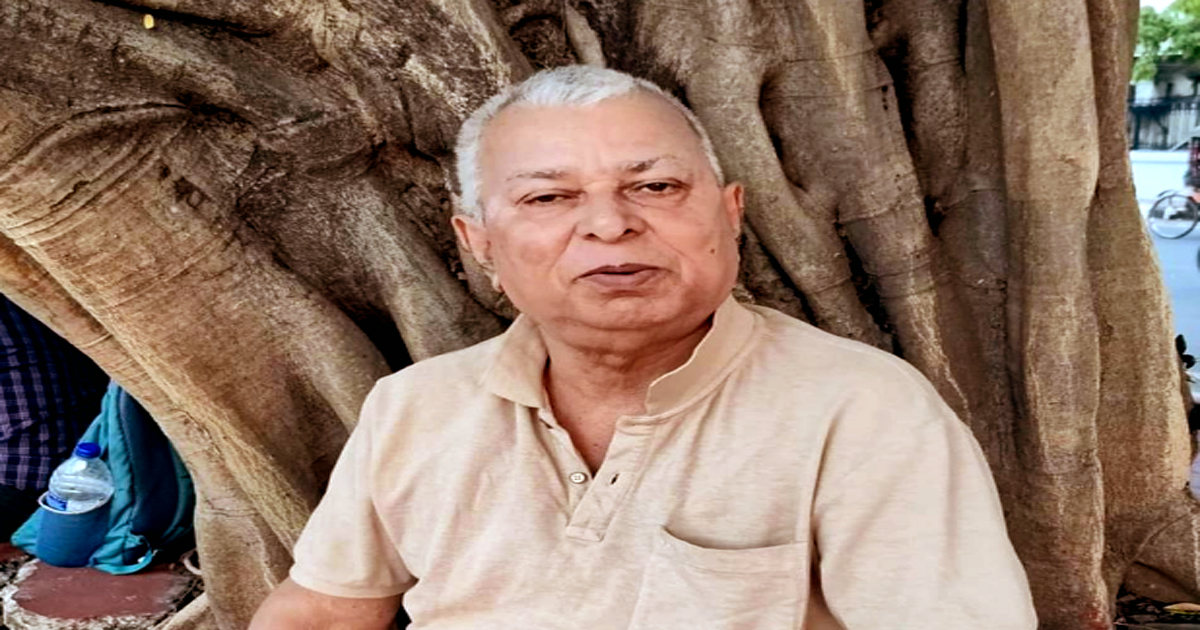

Biswanath Bhattacharya

October 4, 2025

There are sacred cows, and then there are the men who become them. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi—Bapu, Mahatma, Father of the Nation—remains embalmed in Indian memory as a near-mythical figure, an exemplar of moral courage and saintly simplicity. Yet beneath that glowing nimbus of legend lies a patch of ashes, a chapter so confounding and—let us not mince words—disturbing that it festers like an unhealed wound in his storied life.

There are sacred cows, and then there are the men who become them. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi—Bapu, Mahatma, Father of the Nation—remains embalmed in Indian memory as a near-mythical figure, an exemplar of moral courage and saintly simplicity. Yet beneath that glowing nimbus of legend lies a patch of ashes, a chapter so confounding and—let us not mince words—disturbing that it festers like an unhealed wound in his storied life.

Let us not be mealy-mouthed: in the twilight of his life, after the death of his wife Kasturba, Gandhi turned his relentless gaze inward and embarked on what he claimed was a pursuit of “purity.” He had taken a vow of celibacy at the age of thirty-seven, pledging lifelong brahmacharya in 1906, and he carried that vow as a talisman against all fleshly frailty. For Gandhi, brahmacharya was not mere abstention from sex but a grandiose philosophy demanding the eradication of every trace of desire from thought, word, and deed—a kind of spiritual acrobatics performed above the abyss of human longing.

The details are not hidden—they are, in fact, matter-of-factly recorded in his own writings. Gandhi slept—repeatedly, purposefully—beside naked young women. Among them: Manu and Abha, his grandnieces, and Dr. Sushila Nayar, his physician. These episodes formed part of a bizarre rite: nude massages, nude showers and co-sleeping stripped of any curtain between his fragile body and theirs, all to prove that he could lie beside sin and emerge unsullied.

To the modern reader, the tableau is nothing short of scandalous. Picture it: the frail, septuagenarian Mahatma, wrapped in little more than a loincloth—or sometimes not even that—sharing his bed with barely grown girls. He called this the conquest of self and even spun it into what he termed “spiritual marriage,” writing that a union based on knowledge could transcend flesh entirely, possible between any two brahmacharis of opposite sex, or indeed between brother and sister.

What drove Gandhi to such extremes? He carried the guilt of childhood scars: he abandoned his dying father to fulfill marital urges and returned to find death’s finality. That guilt calcified into a toxic suspicion of bodily pleasure. In his eyes, desire was rot in the soul, and brahmacharya the last, most excruciating penance against it.

His experiment unfolded in the harsh glare of a nation’s crisis. As Partition bloodied the streets, he turned his personal crucible into the nation’s potential salvation. In Noakhali, during the height of communal carnage in late 1946 and early 1947, he spent nights with Manu Gandhi—then twenty years old—and Abha in a makeshift bedroom, testing his vow under the very roof that trembled from Hindu-Muslim strife.

The consequences were both immediate and insidious. Aides recoiled and some fled his ashram, the press, cowed by reverence, barely whispered. Even Jawaharlal Nehru confessed to being appalled. Sardar Patel warned that the scandal threatened to undermine Gandhi’s moral authority and erode the public’s faith in his leadership.

And the women? Manu’s diary describes more than mere tests of restraint—she recorded moments of physical affection, hugging and kisses exchanged in the dark of shared beds, with Sushila Nayyar quietly observing. Abha, too, clung to him with childlike devotion, carrying scars we can only guess at. Manu herself died at forty-one, her life marked by illness and isolation, the diary’s pages sealed until decades after Gandhi’s assassination, when they surfaced to confront a saint’s tarnished silhouette.

Historians groping for moral clarity call the experiments “inexplicable” and “indefensible.” Some psychoanalysts even diagnose Gandhi with a form of “vulva envy,” a yearning to transcend gender binaries by becoming both mother and ascetic—an image that veers into the grotesque, the absurd.

Strip away the sepia tones of reverence and the episode stands staggering in its perversity. Were such revelations to break today, hashtags and global outrage would ignite in a heartbeat. The optics—of power, innocence, nudity and sanctimony—would provoke criminal investigations rather than reverent silence.

Yet Gandhi’s time was a different country. His obsessions, however twisted, sprang from a tormented soul seeking the absolute. By his own lights, the experiment was self-mortification; by ours, it was a grotesque misstep.

Here, then, is the paradox of the Mahatma: a saint who stumbled, a messiah who muddied his own halo. His legacy is not granite, but mirror—a reflection of humanity’s loftiest dreams and its ugliest confusions. As Orwell observed, Gandhi’s “smell” was cleaner than most. Yet even the purest incense rises from something that has burned. We cannot worship the ashes without remembering what was consumed in the fire.

আরও পড়ুন...